What we see in this image

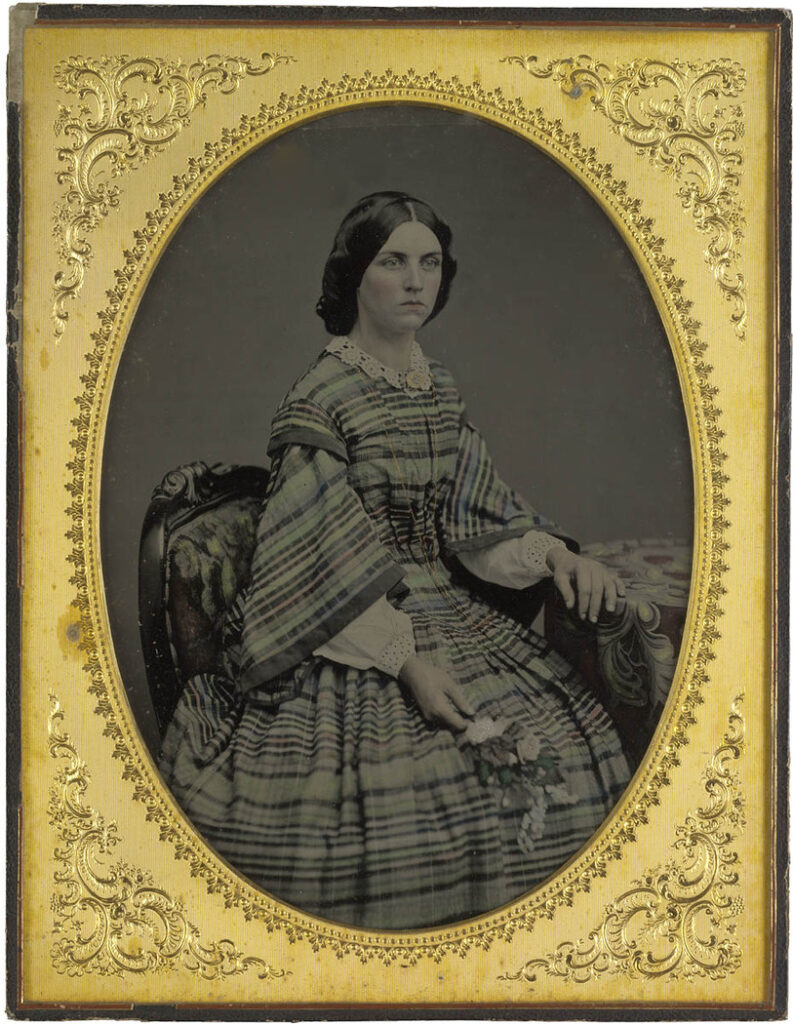

In this right facing, ¾ length hand-coloured ambrotype portrait, the unknown female subject is posed with one hand holding a small posy of [silk] flowers in her lap. She is seated on distinctive floral-upholstered chair with the other hand resting on a small table covered in a similar floral-patterned plush cloth – both the chair and the plush cloth are known studio props of the Sydney-based (American-trained) photographer Thomas Skelton Glaister. From April 1855 Glaister’s American and Australian Daguerreotype Gallery was located at 100 Pitt Street and concentrated its studio portraiture work on Sydney society’s elite. Although Glaister’s photographs were expensive, he offered hand-colouring for no extra charge and quickly garnered a reputation for high photographic standards, producing portraits which were guaranteed never to fade.

The unidentified sitter wears a summer day dress in a fashionably gauzy, tartan-patterned, light-weight cotton fabric (possibly organdie) with the stripes arranged in a horizontal placement to accentuate the breadth of the silhouette – across the bust at the shoulder, around the width of the sleeves and the fullness of the plain, bell-shaped skirt. Her softly-pleated jacket bodice is buttoned to the neck, worn with a narrow lace collar fastened with a [gold] brooch, and caught in a series of tucks below the bust, bringing the fullness in at the waist and sewn down to form a deep point. The sleeve caps and cuffs of her ¾ length ‘pagoda’ sleeves are trimmed with contrasting bias bands of plain [organdie] and left open below the elbow above full white cotton undersleeves, or ‘engageants’, with white-work embroidered cuffs. The long, fine-linked gold chain around her neck may suspending a watch which would usually be tucked into a small ‘watch’ pocket set into the waistband of her dress.

She wears her centre-parted dark hair in the popular ‘bandeau’ style with smoothed front sections wrapped over her ears and pinned behind. The remainder of her hair is arranged in a large, twisted roll forming a ‘halo’ around the crown of her head, its shine suggesting that it has probably been oiled.

What we know about this image

The fashions of the 1850s demanded a horizontal emphasis, enhanced by the use of light-weight fabrics with patterns printed or woven in horizontal orientations. The invention in 1856 of the light-weight steel ‘cage-crinoline’ – hooped bands concentrically suspended from the waist by a series of tapes or sewn onto a single petticoat – reduced the weight of women’s clothing by replacing layers of horsehair-stiffened (crinoline) petticoats without any loss of volume. As cage-crinolines could be produced quickly and cheaply they became the first fashion to be universally adopted by all ages and classes. Light-weight fabrics ensured a buoyancy of movement that enabled crinoline-supported skirts to attain an imposing width by the end of the decade.

PHOTOGRAPHER:

Thomas Skelton Glaister (1825-1904) had worked for the Meade Brother’s photographic studio in New York from about 1850 to 1854, before travelling to Australia to work for Meade Brothers’ Melbourne branch at 5 Great Collins Street. Glaister moved to Sydney from Melbourne in April 1855, establishing his own studio which he called the American Australian Portrait Gallery.

On Tuesday 4 Dec 1855, Thomas Glaister advertised his ‘American and Australian Daguerreotype Gallery’ on the front page of Sydney’s The Empire newspaper, describing his:

splendid Photographic Rooms, with one of the best arranged and largest skylights in the colonies, at 100, Pitt-street, next door to the Royal Victoria Theatre, where he is now producing likenesses which are pronounced by good judges to be vastly superior in delineation, boldness, and the most lifelike to any ever before taken in this colony…Mr. G. has one of Haydon and Co.’s quick working cameras (the quickest now made), the only instrument of the kind in this country, by which pictures are taken in one fourth of the time required by other cameras…

On 5 January 1856, The People’s Advocate reported:

Having recently paid a visit to Mr. Glaister’s American and Australian Portrait Gallery, next door to the Victoria Theatre, we must pronounce it as the most complete and best arranged studio for taking likenesses in the photographic style, we have yet seen in Sydney…

Glaister also provided advice for sitters on clothing that would reproduce well including the suggestion that ’…figured dresses with strong contrasts take well…[but] bonnets seldom should be worn, as they shade the face, and the style changes…’

AMBROTYPE:

By 1856 the daguerreotype had been superseded by a new wet-plate photographic process on glass known as the ‘ambrotype’ which quickly became the more fashionable process. Brought to Sydney in 1854 by James Freeman of Freeman Brothers photographers in George Street, this special type of collodion process was faster than previous methods, with an exposure time less than 10 seconds, and produced a glass negative which, when placed against a dark background, created the optical illusion of a positive image without the reflective issues of the daguerreotype. It was a quarter of the price and could also be coloured. The ambrotype proved popular with the middle classes but, like the daguerreotype, it was destined to be short-lived as copies could not be made.

Thomas Glaister was the finest exponent of the ambrotype in Australia. In 1857 he advertised that his ambrotypes were twice the size of any other in Sydney and impervious to fading due to his exclusive enamelling process which he claimed not only fixed the colours but added a ‘brilliancy to the picture…having all the transparency of miniatures on ivory’ (SMH, 21 November 1857).

COLLODION

The collodion positive, or ‘ambrotype’, was made by coating glass plate with a viscous liquid known as ‘collodion’, made by dissolving guncotton in alcohol and ether which, after the chemicals in the emulsion evaporated, left a thin clear light-sensitive film on the plate. This process required photographers to coat, expose and develop their plates while still wet (hence the term ‘wet-plate’ photography) working quickly before the collodion dried and lost its light-sensitivity. Photographers were slow to realise that the collodion negative could also be used to produce multiple positive prints which, once they did, would change portraiture forever.

Print page or save as a PDF

Hover on image to zoom in

1858 – ‘Unknown Woman’

Open in State Library of NSW catalogue

Download Image

| Creator |

| Glaister, Thomas, fl. 1854-1870 (attributed) |

| Inscription |

| Verso: ‘m/a 6776’ in pencil |

| Medium |

| Photograph |

| Background |

| none |

| Reference |

| Open |

| See also DL Pa 64 |