What we see in this image

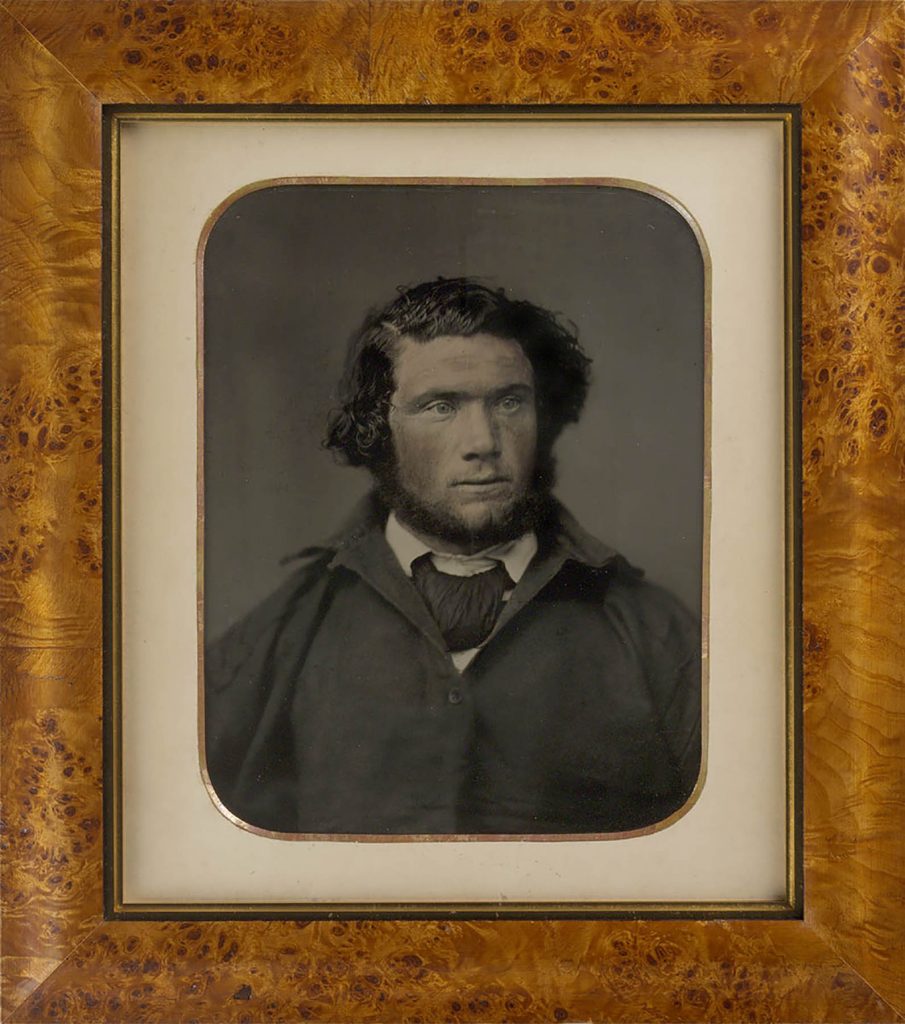

This ¾ length double portrait shows Jane Agnes Nobbs, aged 21, and Ann Naomi Nobbs, aged 19, great-granddaughters of Bounty mutineer, Fletcher Christian. The images is one of a series of photographs of the Pitcairn Islanders taken, following their removal to Norfolk Island in June 1856, at the time of the visit of the Governor-General Sir William Denison in late 1857; the specific circumstances of this quite extraordinary photographic session, on 25 September 1857, are described in a letter from the photographer to the Rev. Thomas Boyes Murray, dated 27 November 1857.

In this portrait, Jane Nobbs is seated on the right, with Ann standing on the left. Both sisters wear loose-fitting day dresses of printed cotton made with a square yoke set in across the shoulder line, with a centre front button closure and narrow band collar, over a voluminous front panel gathered into the yoke above the bust to create a cascade of fabric falling to the floor. In a surprising concession to current trends, the ¾ length sleeves are cut in the fashionable ‘pagoda’ shape and the women wear their dark hair in the popular ‘bandeau’ style, with smooth front sections wrapped over their ears and pinned behind into a low bun at the nape of the neck. They also wear a plain or patterned scarf tied around their necks. Perhaps to aid the photographer in achieving sufficient contrast in the image, Jane has draped a plain dark [silk/polished cotton] shawl around her shoulders.

According to the Rev. T.B. Murray, ‘The features of the Pitcairners, both men and women, were more strongly European than I had expected. They were tanned and brown skinned, but most were no darker than sunburned, brown-haired Englishmen. The women looked more Polynesian than the men… [and] wore loose cotton dresses..’, Pitcairn – The Island the People and the Pastor, 1859, London, England.

From the early-nineteenth century, missionaries introduced Pacific communities to highly modest versions of a type of European women’s ‘undress’ known as the ‘Mother Hubbard’ – so called after the nursery rhyme illustrations of ‘Old Mother Hubbard’ published from 1805 – in the belief that the adoption of such clothing by indigenous groups was a sign of civilised Christian behaviour. These long, loose-fitting dresses with full sleeves and a high- yoked neckline were customarily made from dark serviceable materials for weekday wear and white for Sundays. Designed to be worn unbelted, this relaxed style of ‘housedress’ eliminated the need for restrictive corseting and was routinely worn indoors by most women, especially during pregnancy, and invalids. It helped revolutionize women’s fashion through its reference to freedom of choice for women, not just in fashion but also in other spheres of life.

What we know about this image

Ann Naomi Nobbs (1838-1931) and Jane Agnes Nobbs (1836-1926) were two of the ten children of George Hunn Nobbs (1799–1884) and Sarah Christian (1810-1899), grand-daughter of Bounty Mutineer, Fletcher Christian. On December 25, 1857, Ann marry Caleb Quintal (1837-1873) on Norfolk Island, raising a family 9 children; Jane married John Quintal on August 25, 1861; the couple had 7 children.

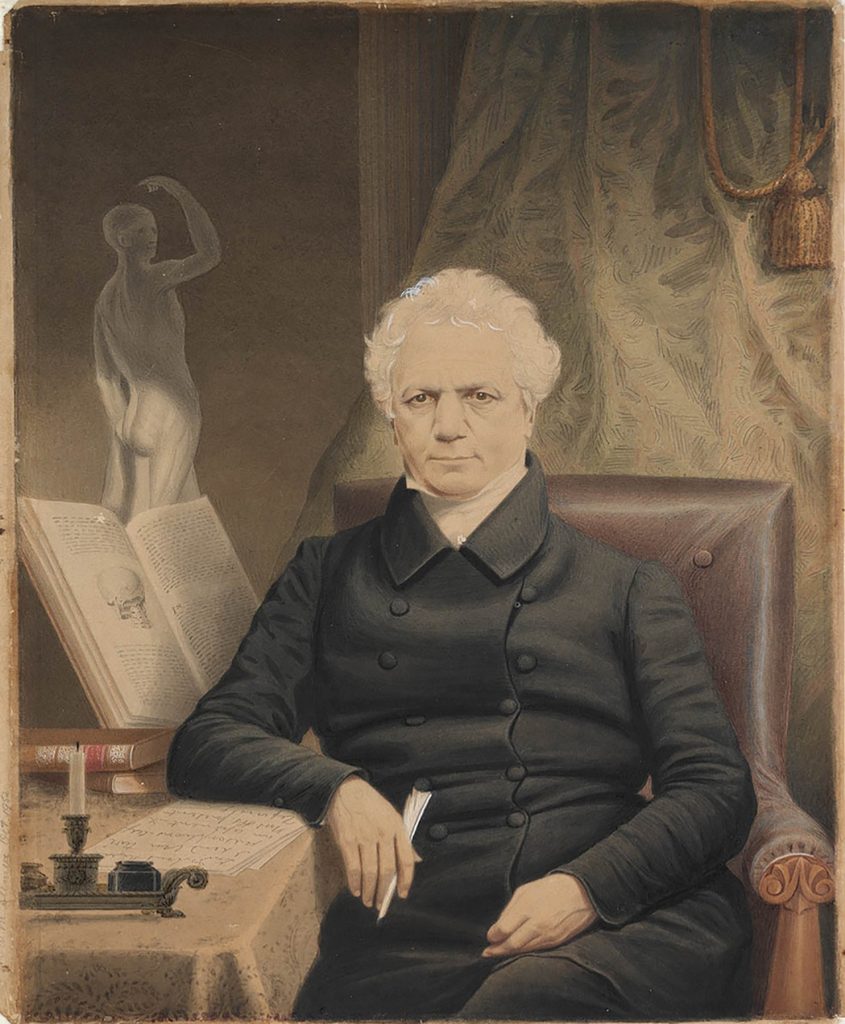

George Nobbs had first arrived on Pitcairn Island on 5 November 5, 1828, at age 28, and married Sarah Christian in Tahiti on 18 October 1829. By 1838 he had become the acknowledged leader of the Pitcairn community. For over twenty years he taught the youth, ministered to the sick and consoled the dying on the Island. Travelling to England, he was ordained as a minister in 1852.

It was largely on the advice of Nobbs and Admiral Moresby (father of the photographer) that the Pitcairn community elected to migrate to Norfolk Island on 8 June 1856, following the suggestion of the Colonial Office that Norfolk Island was ‘fit for the reception of a small body of settlers now existing at Pitcairn Island’. Sir William Denison (1804-1871), Governor-General of Australia (1855 to 1861), was authorized to control the removal and resettlement of the whole community of 194 persons.

On 25 September 1857, the ‘Iris’, arrived at Norfolk Island with Sir William Denison and naval officer and photographer Matthew Fortescue Moresby (1828-1918) aboard. Denison recorded that, since ‘Moresby had brought a photographic apparatus on shore, I decided to get good likenesses of as many of the islanders as we could … After a good deal of trouble we got several groups of both males and females; and here and there single photographs’.

Moresby had visited Pitcairn Island several times during the early 1850s, and enjoyed ‘taking walks over the Island, sketching, talking and singing’, becoming very fond of the Pitcairners: ‘truly a more innocent and delightful race could not exist’. On this occasion Moresby himself reported that, ‘I turned Mr Nobbs’ study into an impromptu dark room and then took some pictures. Of course in taking groups with children, some of them moved’. In 1859, the Rev. T.B. Murray, confirmed that ‘ten well executed photographic groups and simple portraits, accomplished by Mr Fortescue Moresby under the above disadvantages, have since reached the author’s hands’.

Nobbs continued his former work as pastor and teacher on Norfolk Island until 1859, when Denison sent Thomas Rossiter to act as schoolmaster and store-keeper, increasing Nobbs’s salary as chaplain. A century and a half later, the descendants of Nobbs and his wife Sarah are among the largest and most influential of the ‘founding father’ families which still dominate most aspects of life on this self-governing island territory.

Ref: (See ML A 2881: G. H. Nobbs papers, 1836-79, http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110362728

Pitcairn Island Recorder, 1838 (SLNSW)

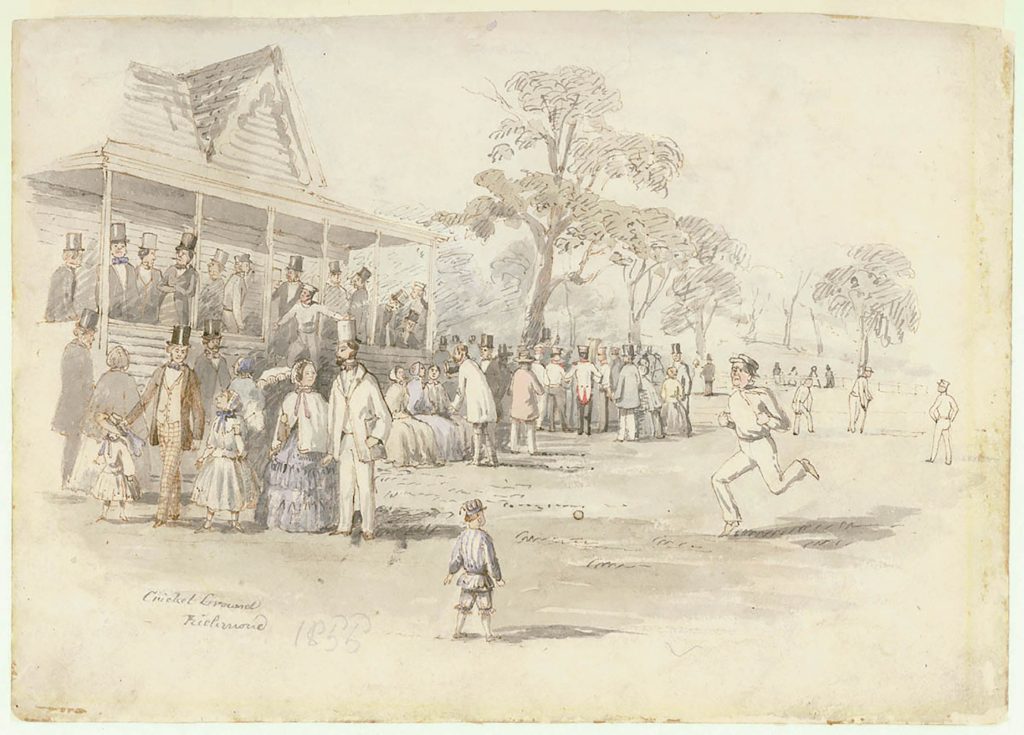

Sir William Denison was Governor General of Australia from 1855 to 1861. Married in 1838, to Caroline, nee Hornby, daughter of a naval officer, Denison took up the post of Lieut. Governor of Tasmania In 1847, bringing with him to Australia his wife and four children, including the sketcher Mary Charlotte Denison.

PHOTOGRAPHER:

Matthew Fortescue Moresby (1828-1918) (known as Fortescue or ‘Forty’), sketcher, amateur photographer and clerk, was the second of the three sons of Admiral Sir Fairfax Moresby and Eliza Louisa, née Williams, of Bakewell, Derbyshire. Sir Fairfax was commander-in-chief in the Pacific in 1850-53 and all his sons served in the region. Moresby was secretary to his father on board HMS Portland in 1852-53, and

In 1856-60 Moresby was based at Sydney, as paymaster-in-chief under the command of Commodore William Loring of the flagship ‘Iris’, where he seems to have begun taking photographs; it is not known from whom he learned the art of wet-plate work but it may have been from his friend E.W. Ward.

NB: Photographs taken by M.F. Moresby on a number of South Pacific islands visited with the Iris, including the Solomon’s, New Hebrides and the Pitcairners of Norfolk Island are found in the Macarthur Family’s Camden Park albums: ML PXA 4358/Vol.1: Album of views, illustrations and Macarthur family photographs, 1857-66, 1879, by various photographers. http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110326756

[Two unidentified groups on a veranda possibly Pitcairn Islanders]

[Four unidentified groups possibly Pitcairn Islanders]

These were, however, not the first photographs to be taken of the islanders. (See A.P.R. October 1956, pp. 588-597 for an illustrated article on Moresby by K. Burke.)

Print page or save as a PDF

Hover on image to zoom in

1857 – ‘Anne Namoi [Ann Naomi] & Jane Nobbs’

Open in State Library of NSW catalogue

Download Image

| Creator |

| Matthew Fortescue Moresby (1828–1918) |

| Inscription |

| Lower edge: M F M |

| Medium |

| Photoprint |

| Background |

| To follow |

| Reference |

| Open |