What we see in this image

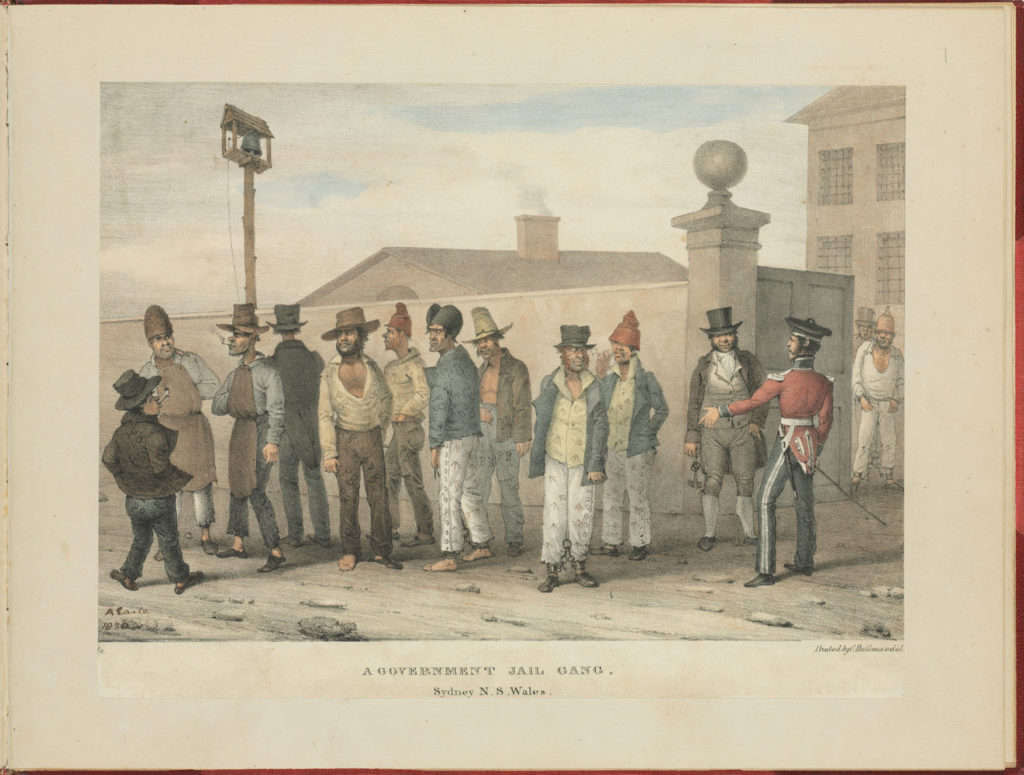

This streetscape records fourteen portrait figures, mostly convicts waiting for the day’s work duty allocation, standing outside the Hyde Park Barracks, on Macquarie Street in Sydney. Opening in May 1819, the Barracks housed a diverse and motley crew of repeat offenders. Augustus Earle’s finely observed view records a wide array of convict garb worn by Barracks inmates including details of the cut and construction of ‘punishment’ trousers worn by chain gang convicts which were made to button on the outside of each leg to enable their easy removal over leg irons, as well as the manner of wearing leg irons when walking. Some convicts used their leisure time to make cabbage tree hats (as worn by the third, fifth and eighth convicts) which were cooler on the head and gave protection from sunburn than the standard issue woollen hats (seen second from the left) which offered no sun protection, or the leather caps with semi-circular flaps (mid-foreground) which could be pulled down to give some sun protection but absorbed the heat. Convicts sent to the Hyde Park Barracks weren’t always lucky enough to be issued with socks or stockings and there was also a chronic shortage of shoes as evidenced by the number of bare ankles and feet in this image.

What we know about this image

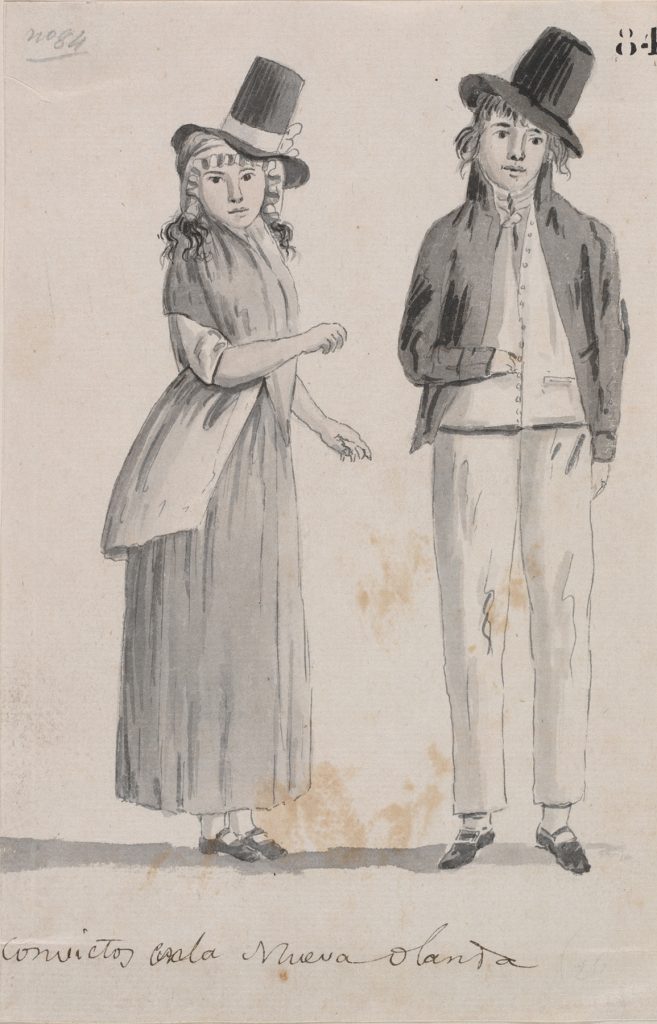

According to evidence supplied to the Bigge Royal Commission in 1819, on landing in NSW each convict received a clothing issue comprising a coarse woollen jacket and waistcoat of yellow or grey cloth, a pair of duck (cotton) or cloth (wool) trousers, a pair of worsted stockings, a pair of shoes, two cotton or linen shirts, a neck handkerchief and a woollen cap. In the 1820s the Board of Ordnance took over the supply of convict clothing and all items made or used by government convicts were marked or stamped with broad arrows or the letters ‘PB’ (Prisoners Barracks). Convicts sent to the Barracks received a further issue of two striped shirts which clearly distinguished the wearer as a repeat offenders, and convicts names and numbers were also written on their clothes to discourage theft or barter.

This work is dated from the time of Augustus Earle’s stay in Australia (1825-1827). It was published in his ‘Views in New South Wales and Van Diemens Land: Australian scrap book’ (1830) with the accompanying text:

‘Every person in England is aware that for certain offences men are transported to New South Wales but there are few, except those who have visited the colony, know how they are disposed of after they reach their places of destination. When they land they do not go to gaol but are assembled in the Prisoners Barracks Yard and there inspected by the Governor, Superintendant (sic) of Convicts and the Officers of the Ship which brought them. And it is truly astonishing to see such men, under such circumstances and after so long a voyage, look and behave so well. They are immediately assigned to such Settlers as may want them, and they accompany their new masters, in the capacity of servants; their ration and clothing is arranged by the Government, and generally speaking they are comfortably off: but for any fresh offence Government take them back, and then they are placed in gangs, and toil at the public works, where they have harder duty, less liberty, and reduced rations and for still repeated crimes, are banished to remote penal settlements. The annexed subject is one of the Government gangs being told out of the barracks for the daily work, and given in charge of a soldier who acts as overseer.’

During the first years of settlement in Australia, clear categories of distinctive convict dress or uniform were never satisfactorily enforced due to irregularities of supply from England. As a result, convicts and free working class people in the colony all wore very similar kinds of clothing largely consisting of basic, uniformly drab, ready-made garments known as ‘slops’ which was the term for any type of coarse loose-fitting mass-produced clothing and the standard dress of the urban working classes at the time. A lack of distinguishing dress meant discipline was difficult to maintain in the colony and this was further exacerbated by the assignment system.

Print page or save as a PDF

Hover on image to zoom in

1826 – A Government Jail Gang, Sydney N. S. Wales

Open in State Library of NSW catalogue

Download Image

| Creator |

| Earle, Augustus (1793-1838) |

| Inscription |

| Imprint LLHS: ‘A. Earle, 1830’ |

| Medium |

| Hand-coloured [engraving] |

| Background |

| Subjects posed outside Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney. |

| Reference |

| To follow |