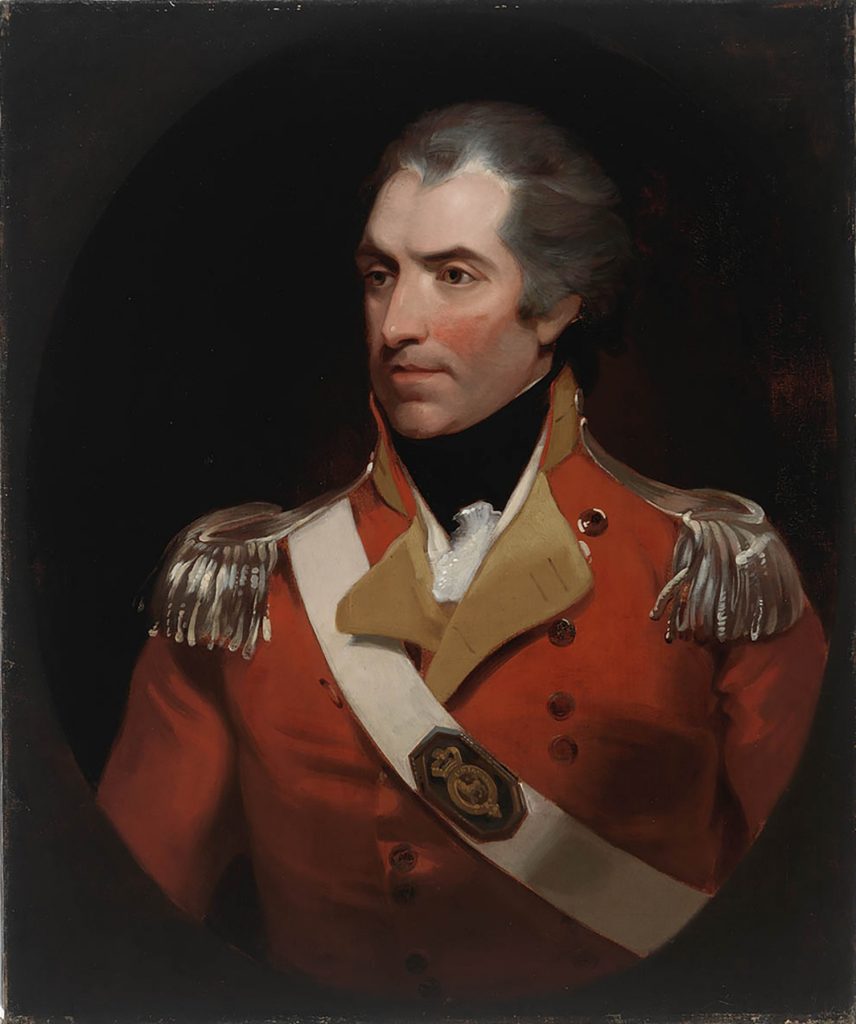

What we see in this image

This caricature records the culmination of events which began at around 6pm on 26 January 1808, when 4000 soldiers of the NSW Corps, under the command of Col. George Johnston, marched from their Barracks, along Bridge Street, to Government House, Sydney, with the intention of arresting Governor William Bligh. It took an hour and a half to find Bligh who had concealed himself, in full-dress naval uniform, upstairs in a servant’s room, where he destroyed documents he did not want to fall into the hands of the mutineers. According to his enemies he was found hiding under a bed.

This image shows these events taking place in a bedroom and witnessed by three soldiers wearing the uniform of the NSW Corps; during the trial in London, Lieutenant William Minchin recalled that on entering the room there were already two or three soldiers there (Sergeant John Sutherland, Corporal Michael Marlborough and Private William Wilford) but that the Governor was standing up.

The soldier leaning down to drag Bligh out from under the bed can be ranked as a corporal by the pair of chevrons, point downwards (since 1802), on the upper arm of his red woollen jacket. The standing figure (far right) is clearly portrayed with a single epaulette on his right shoulder denoting the rank of Lieutenant. This is, therefore, most probably Lieut. William Minchin (1774?-1821). He also wears the top hat of an officer with black trousers tucked into tasselled ‘hessian’ boots, and carries a sword at his side.

The two soldiers wear tall, black cylindrical ‘stovepipe’ shakos with peaked visor and a brass regimental badge attached to the front. This type of shako was worn by British Army infantrymen from around 1799 until the end of the Peninsular War (1808-1814). The red and white side plume, or cockade, worn on the left side of the shako behind a black cloth rosette, enabled commanders to distinguish who was who on a battlefield; white at the top of the plume indicated ‘Infantry’ and red at the base ‘English’. The men also wear white cross belts over their red woollen jackets, above grey trousers and low cut, flat black shoes, or pumps.

What we know about this image

The ‘Arrest of Governor Bligh’ is an image of propaganda. Despite its being the only surviving visual account of these event, its content must be treated with some scepticism. The watercolour first came into the possession of the NSW Government in 1888, from the descendants of Lieutenant Colonel George Johnston, and was transferred to the Mitchell Library in 1934.

It is likely that this caricature is the one commissioned from an unknown artist by Sergeant Major Thomas Whittle (c.1764-1822), a NSW Corps soldier known to have participated in the Bligh’s arrest on 26 January 1808, with Lieut. William Minchin (1774?-1821), who appears as the standing figure on the far RHS of this image. Sergeant Whittle is believed to have displayed this image in his house, enshrined between two candlesticks, a couple of days after the rebellion.

The genesis of the watercolour of Bligh’s arrest appears to have been a dispute that blew up between Bligh and Whittle. According to contemporary newspapers accounts of the incident, it seems that Bligh had asked Whittle to remove his house because it stood in the way of town improvements. Whittle protested and Bligh angrily abused him. Possibly in the spirit of revenge, Whittle, who later gave evidence at the trial in London as having seen the Governor just after his arrest, commissioned this drawing of Bligh being pulled by soldiers from under the bed.

Print page or save as a PDF

Hover on image to zoom in

1808 – The arrest of Governor Bligh

Open in State Library of NSW catalogue

Download Image

| Creator |

| To follow |

| Inscription |

| On back: ‘Sketch of Bligh’s / arrest by / Lieut. Minchin’; ‘Govn Bligh’ ; and ‘Govn. Bligh under the Bed’ |

| Medium |

| Watercolour |

| Background |

| Shows interior view of Government House, Sydney. |

| Reference |

| To follow |